The origin of Dormeuil’s luxury fibres

The history of the house Dormeuil is interwoven with the constant search for the rare and luxurious. Dominic Dormeuil explores numerous breeding farms around the world each year to select the most precious fibres and produce exceptional fabrics.

Vicuña

The fibre of the gods

A slender animal with a fawn and white coat, the vicuña has a magnificent treasure in its exceptionally fine fleece, which adorns it in unrivalled fineness and softness. Overhunted in the 1960s for its fleece, a protection programme in Peru ensured the resurgence of the Queen of the Andes. Today, vicuñas roam freely in small groups in their natural territory.

In common with its fellow Andean species, the alpaca, guanaco and llama, the vicuña belongs to the larger camelid family which originated from the region of modern-day North America. Of all the camelids, the vicuña gives by far the best wool. With a diameter of 11 to 14 microns and a length of around 30 millimetres, the fibre from its fleece is the number one precious wool in the world.

Each vicuña gives 300 grams of wool per harvest: wonderful gossamer wisps of 12 microns in diameter. In addition to its fineness and its length, which gives it a particular sheen, vicuña fibre has a beauty and brilliance that derives from its unmatched brightness.

Discovering the vicuña involves a visit to the Jujuy province in Northern Argentina’s Salta region, to experience the terrain and the altitude. This incomparable landscape is home to the vicuña. Dormeuil settles in for a rare event, the shearing of this small member of the camelid family whose wool is a gift from the gods. The animal is protected and respected, and every effort is made to treat it with the utmost reverence, prudence and consideration.

The chaccu

A slender animal with a fawn and white coat, the vicuña has a magnificent treasure in its exceptionally fine fleece, which adorns it in unrivalled fineness and softness. Overhunted in the 1960s for its fleece, a protection programme in Peru ensured the resurgence of the Queen of the Andes. Today, vicuñas roam freely in small groups in their natural territory.

The Princess of the Andes

With its slender neck and huge dark eyes framed with long eyelashes, the vicuña has a unique grace and charm.

Built for the high plateaux

Vicuñas are shorn every two years and are ringed for identification from one year to the next.

Vicuñas are shorn one at a time using electric clippers. Shearing takes no more than a few minutes to limit the stress to the animal, which is immediately released. Vicuñas are shorn every two years and are ringed for identification from one year to the next.

Mohair

An atypical wool

Originating from Turkey, the mohair goat has been renowned since ancient times for the whiteness and the diamond sheen of its fibre. The goat’s curly fleece gives the fibre outstanding elasticity, making weaves highly resistant to creasing. Soft yet durable, above all it has an unparalleled sheen.

More than two hundred years ago, breeders in the Camdeboo region at the tip of South Africa, close to Cape Town, began to produce a rare variety of goat with an immaculate white coat, the mohair goat. The secrets of rearing these goats have been handed down from generation to generation. The animals are fed with the utmost care and their fleece is regularly treated with natural oils to make it sleeker and more luxurious.

Qiviuk

Musk ox wool

Who would have thought that a fibre so ethereal, with the lustre of silk and the softness of cashmere, could be ages old?

The prehistoric colossus that is the Arctic musk ox gives us qiviuk, one of the most precious wools ever produced.

As remarkable as it is rare, the musk ox is an ancient animal that survived the last ice age. A rugged, powerful beast, it journeyed through prehistory while mammoths and other large mammals disappeared from the surface of the earth. When the earth warmed up after the last ice age, around 12,000 years ago, the musk ox followed the glaciers to the Arctic, where it is found today.

Softer than cashmere and warmer than wool, qiviuk has astonishing properties. This exceptionally fine and splendid fibre protects the musk ox from the extreme cold of the Canadian Arctic.

Qiviuk is amongst the rarest and most precious wools ever produced. Worldwide production fluctuates between 5 and 8 tonnes a year, 3,000 times less than cashmere! Furthermore, its supply can never be guaranteed. Currently, a good proportion of qiviuk comes from traditional hunting in Greenland, which is strictly controlled and respects the natural ecological balance.

Musk oxen live in small groups. They are extremely timid and it is difficult to get close to them, especially in the regions where they are hunted. As soon as musk oxen sense danger, they adopt a defensive formation with their young at the rear. They will charge if they feel cornered, but will prefer to run away after observing for a few seconds.

The musk ox cannot tolerate hot weather and once the spring arrives, it sheds its dual coat on the rocks and in the undergrowth. As such, between May and June, it is not unusual to find quantities of qiviuk in small tufts attached to the branches of the dwarf willows of the tundra that the herds pass through. The wool is then collected by small producers, but significant effort is needed to clean it.

Combing a skin to obtain qiviuk wool in the workshop of Anita Hoegh and Birthe Melin Andersen. To achieve this, pelts are attached to wooden cylinders. Firstly, the hair must be cut from the fur to a depth of around seven centimetres, so that the undercoat is accessible for combing.

Winter qiviuk is incredibly clean and needs little in the way of treatment. As a result of the bitter cold, it has no parasites and the thick hair that covers the qiviuk undercoat prevents penetration by thorns or dirt. Every skin has to be combed for over an hour to extract between 600 g and 1.2 kg of qiviuk.

Linen

A perfect summer fibre

European linen has traditionally been recognised as the most beautiful linen in the world. It owes its tremendous growth to the combination of modern technology with unique expertise. Derived from the flax plant, which is sensitive to soil quality and climate conditions and therefore difficult to grow, linen is a perfect summer fibre. Providing insulation in winter and breathability in summer, linen is ideal for relaxed jackets.

Cotton

Exceptionally soft with lasting quality

Dormeuil uses cotton fibre grown in Egypt to produce very specific qualities such as velvet, combining it with cashmere and silk for summer fabrics. The Egyptian cotton used by Dormeuil is acknowledged to be the finest in the world and is renowned for being soft and hard-wearing.

Taewit wool

Precious wool from the Heavenly Mountains

Taewit wool comes from the Kyrgyzstan goat, which lives at an altitude of 3,500 metres in the pastures of the Heavenly Mountains. It produces one of the world’s most precious fibres. This incomparable fibre is as fine as the most beautiful cashmeres, as soft as pashmina, and as smooth as silk.

Here in the alpine pastures of Song Kul lake, at an altitude of 3,200 metres, the most beautiful cashmere goats are raised. While the backdrop is picture-postcard perfect, the climate conditions can be extreme. The pastures see the worst of all weathers – storms, hailstorms, torrential rain and blizzards – and as is always the case, these extreme climate conditions to which the goats must adapt produce the very best down.

The taewit wool harvest is the product of long months of cold, snow and ice: a harvest of immaculate down, a true gem which is hidden each spring under the thick hair of the Kyrgyz goats.

After the fall of the Soviet regime, many Kyrgyz families left to fend for themselves became involved in farming for wool production. The return to traditional farming techniques created a strong bond between the nomads and their animals, which are still treated with the utmost care.

Mokeshof keeps constant watch over his flock with his old binoculars, doubtless one of his most prized possessions. Most Kyrgyz nomads have adopted modern clothes imported from China, but have continued to wear the felt hat that is characteristic of their culture.

In the mountain pastures of the Heavenly Mountains, Dominic Dormeuil carefully examines the unique fibre of Kyrgyz goats.

Pashmina

The wool from the end of the world

Perched at an altitude of over 3,500 metres and bordering Kashmir and Tibet, the ancient Himalayan kingdom of Ladakh is at the heart of the ancient pashmina wool road. Pashmina goat wool is amongst the world’s most precious wools.

A rare fibre harvested in the heart of the Himalayas, also known as the ‘Kingdom of Snow and Ice’. The pashmina goat is protected by several layers of an extraordinarily fine coat of 14 to 19 microns in diameter. They are raised by the nomads of Ladakh at an altitude of over 4,800 metres on the high plateaux of Changthang, where few travellers venture.

The rarity, softness and incredible fineness of pashmina wool – a pashmina hair is six times finer than a human hair – make it extremely precious.

The fibre comes from the undercoat of the domestic goats of Changthang, the high plateau of western Tibet. Like their cousins in Kyrgyzstan and the Gobi, they can only be farmed by shepherds moving between summer and winter pastures in wilderness areas. And so, for centuries, perhaps longer, the Changthangi nomads have been producing pashmina wool at an altitude of nearly 5,000 metres for the master weavers of the Kashmir valley.

A weaver inspects a pashmina wool lot in the carding and combing workshop in the town of Kulu. The most beautiful weaves are made in the neighbouring Srinagar valley, the result of the specific humidity required for traditional spinning and weaving of fine pashmina fibres.

A large herd of goats crossing an ice field at over 5,000 metres, on their way through a col between the Changthang plateau and the high valley of Lahaul. At this altitude, winter temperatures are frequently as low as -30°C, with extreme winds.

Cashmere

An exceptional product

In the heart of Mongolia’s Gobi Desert, rugged nomads produce the very finest cashmere wools. Rare and precious, cashmere wool is incomparably light and soft. The region is one of the birthplaces of goat-rearing and as has always been the case, wool goats move between their summer and winter pastures where they are still free to roam.

Seasonal temperatures at an altitude of over 4,000 metres on the Tibetan plateau or in the Gobi Desert can range from -40°C to +40°C! The goat has adapted to these conditions and its long coat helps it to withstand the harsh climate.

The cashmere fibre is harvested from the goats’ chests once a year by the nomadic tribes of the region. The harvest is no more than 150 g of fibres per animal.

Today, there are three colours of cashmere goat – black, tan and white – which give dark grey, grey-brown and white wools respectively. The white goats are originally from the Gobi and the mountain shepherds of Arkhangai have to buy goats from their desert counterparts to ensure this prized quality in their own herd.

Tumenjargal and his wife inspect the white cashmere they have just collected. Their yurt is one hour’s journey by motorbike from Shine Jinst village, in one of the most remote regions of the Gobi Desert. The couple own seven hundred white goats, around twice as many as the average for farmers in the region.

Extreme climate conditions

The farmers and their herds live in difficult climate conditions where extreme episodes of bitter cold and heatwave are not infrequent.

Shine Jinst white cashmere goats

Farmers think that the family of white goats specific to the Gobi Desert originates from this region. Shine Jinst is the only place where the whole of the goat population is white.

Gobi Desert wool is one of the most beautiful and sought-after of the many qualities of cashmere wool. The farmers around the village of Shine Jinst are also known throughout the country for the goats specific to this region, whose fibre is the whitest and finest in the world.

Silk

A prestigious natural fibre

A natural textile fibre of animal origin, silk comes from Bombyx mori (mulberry silkworm) cocoons. Asia is home to the world’s finest silk. Its production remains a well-guarded secret. Dormeuil blends silk with other exceptional fibres such as cashmere and pashmina to create ever more luxurious fabrics.

Merino

The noblest of wool sheep

The southern hemisphere countries of New Zealand and Australia offer exceptional conditions for the Merino. In the face of fierce worldwide competition, some breeders took a gamble on producing wools of unrivalled fineness.

The Merino sheep requires constant care and particular kinds of pasture, far removed from any form of pollution, and these are found primarily in southern Australia, Tasmania and New Zealand. Merinos involve more work than any other breed, requiring unswerving passion and devotion to the task from the breeder. Their toil is not always appropriately valued by the market, but as lovers of fine wool, they reap their reward at each shearing, when the fleeces reach the desired fineness.

Purebred Merino rams need a particular climate and pastures. Until the shearing period, flocks are free to roam and the breeder may face several hours’ walk to herd them.

Australia is the world’s leading producer of Merino wool, with the wool produced in Tasmania considered to be one of the country’s very best. Originally from Saxony, the Saxon Merino sheep is the aristocracy of wool sheep, so to speak. It is a high-maintenance animal and only very few breeders work with a flock of purebred Saxons.

The Taylor family

In Winton, the Taylors are enthusiastic about their flock of two thousand merinos which they farm on more than three thousand hectares of gently rolling valleys.

A New Zealand Merino ram

A proud young Merino ram on the hills above Dick Bell’s farm on the outskirts of Blenheim. As a timid and gregarious animal by nature, it is unusual to be able to get close to a lone Merino.

Focus on Merino fibres

The quality of the wool is judged on the basis of the colour – which should be as pale as possible – its elasticity in proportion to the crimp density, and its fineness, as determined by the diameter in microns or micrometres.

Destinations

From fibre to yarn

After shearing or harvesting, the fibres go through a number of treatment steps to transform them into high-quality yarn for weaving. Sorting and initial cleaning are undertaken by artisan breeders. The next steps in the production process take place, in the hands of the best weavers and leading experts.

Sorting the fibre

Artisans manually sort each fibre depending on its fineness, separating out the fibres into a number of qualities.

Cleaning the fibre

The fleece is washed to remove impurities such as grease, dirt and straw.

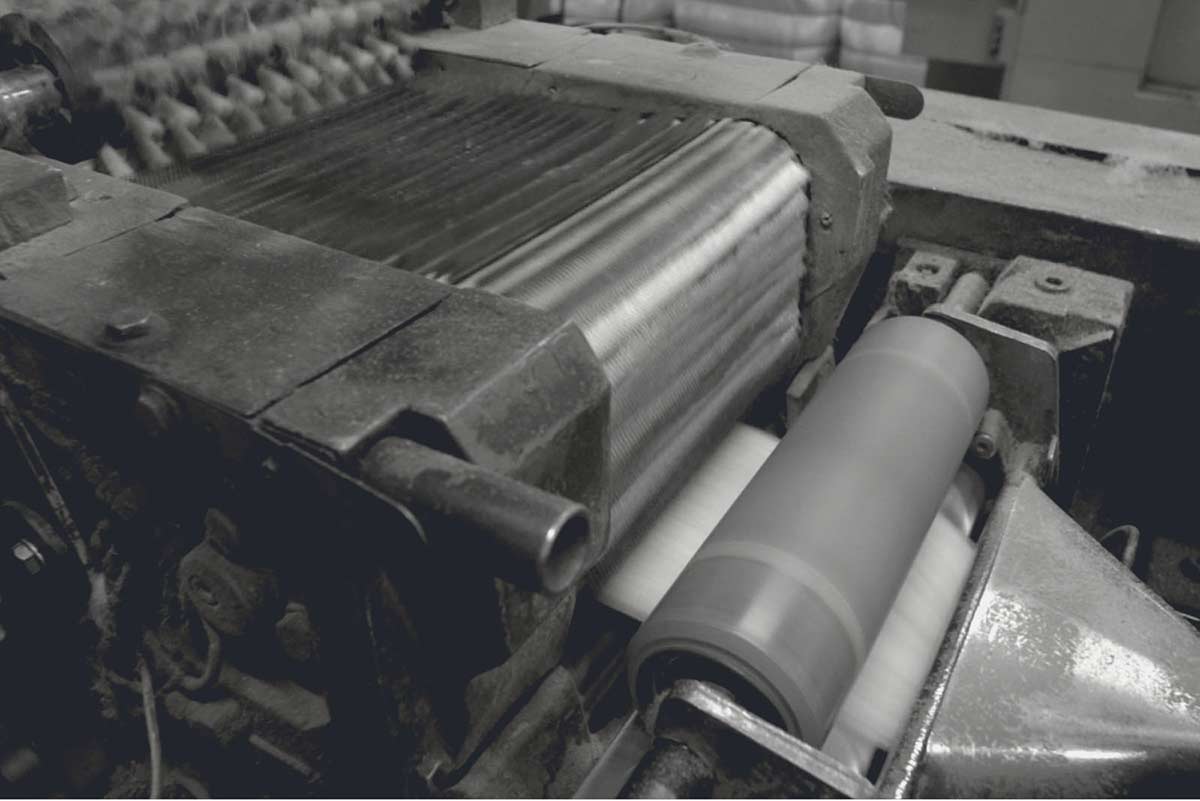

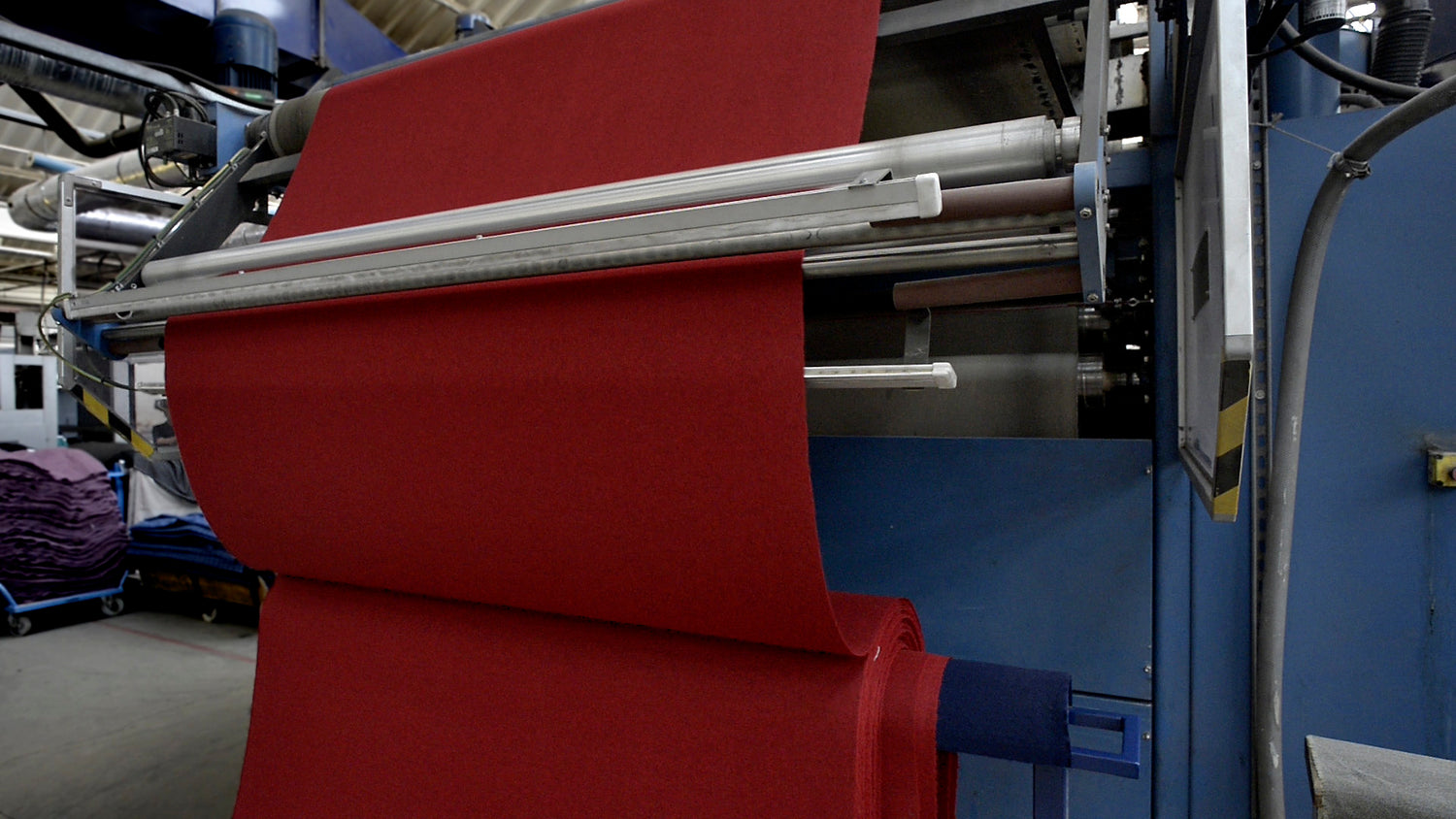

Carding the fibre

The wool fibres are separated, untangled and ventilated to give the carding strand. It is at the carding stage that blends of fibres can be made.

Combing the fibre

Long fibres will be combed to align the fibres in parallel and the shorter fibres are then removed.

The « Top »

A continuous strand of clean fibres called the « Top » is obtained.

Dyeing the « Top »

The strands are dyed in bulk prior to spinning.

There are different kinds of dyeing

• Top dyeing: this consists of dyeing the fibre strands prior to weaving.

• Yarn dyeing: this consists of dyeing the spools of raw wool thread after spinning.

• Piece dyeing: this is generally the least expensive technique. The product is woven in its natural colour and then dyed in an autoclave.

Spinning the fibre

Spinning consists of twisting the natural fibres to obtain a more durable continuous yarn, transforming natural wool fibres into a fine, smooth, compact yarn.

There are two methods of spinning:

• Worsted spinning (long fibres): the fibres are combed during spinning to remove the airspaces and more twist is applied, creating a fine, smooth, durable yarn. This method is used primarily for men’s suits.

• Woollen spinning (short fibres): the fibres are not combed when they are spun, and little twist is applied. This gives a soft, lofty thread. This method is used primarily for jackets, coats and knitwear.

From yarn to fabric

Renowned for its exceptional properties, Yorkshire’s water provides a unique advantage when it comes to fabric finishing. All our fabrics combine traditional methods and innovative techniques for a soft finish and impeccable drape.

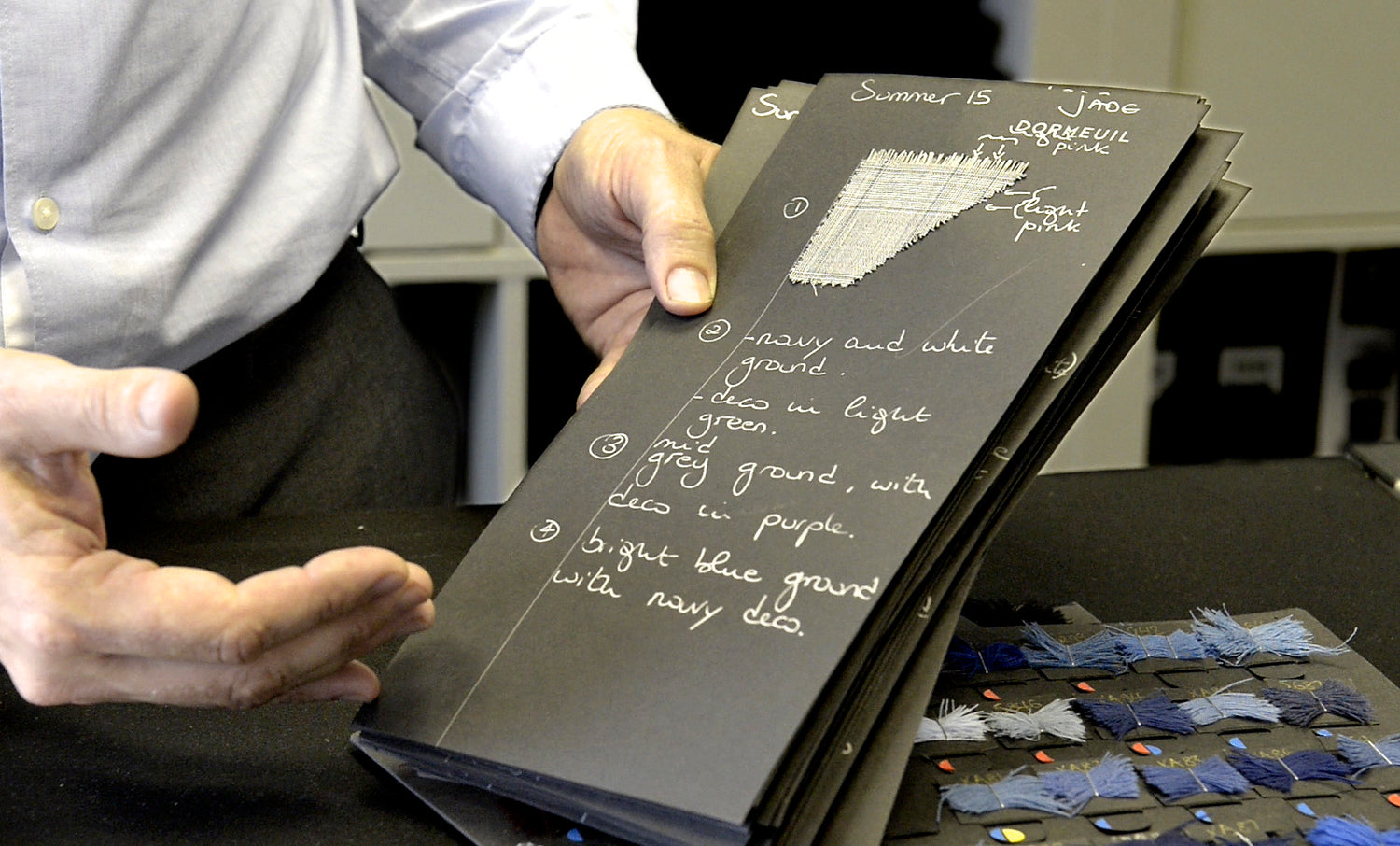

Bringing a collection to life

The fabrics in each collection are created by Dominic Dormeuil and his Design team, before being prototyped at Dormeuil’s premises in Yorkshire, England. The house Dormeuil designs a new fabric collection twice a year.

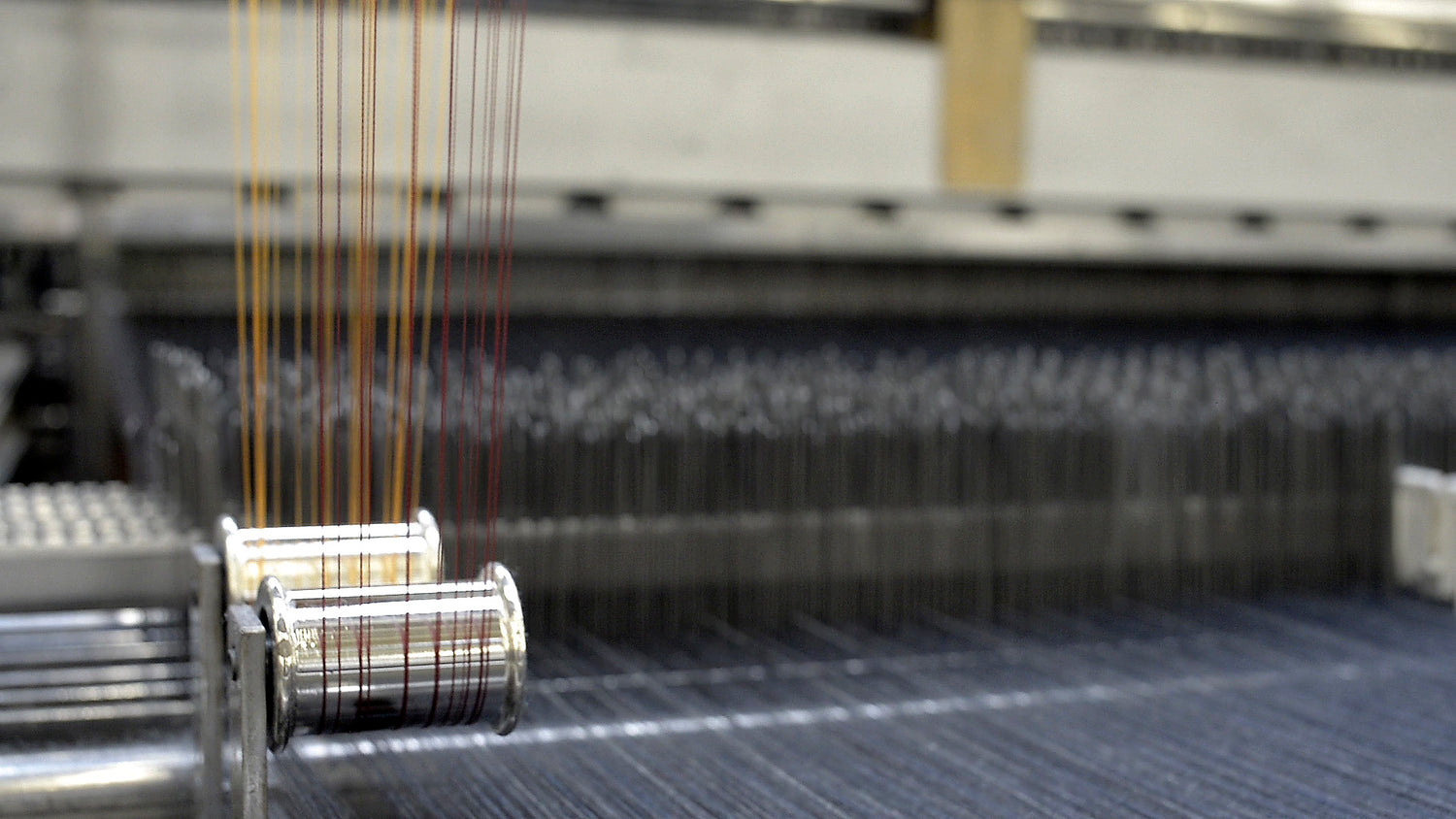

Warping

Warping consists of unwinding the yarn cones onto a warp beam ready for weaving. The warp yarns are wound at an even tension and in parallel in a specific order, a process known as drawing-in.

Weaving

The weave is produced by interlacing warp (vertical) yarns and weft (horizontal) yarns at a specified frequency.

There are more than one hundred types of weave, with three being used most widely.

• Plain weave : the warp and weft are aligned to form a simple criss-cross weave. Each weft thread crosses a warp thread by passing over it, then under the next one, and so on in regular fashion.

• Serge weave : This type of weave is created by passing the weft thread under two warp threads then over two more, offsetting by one thread for each pick to give the fabric its diagonal effect.

• Satin weave : The satin weave is characterised by four or more weft threads floating over the warp thread or conversely, four or more threads passing under it.

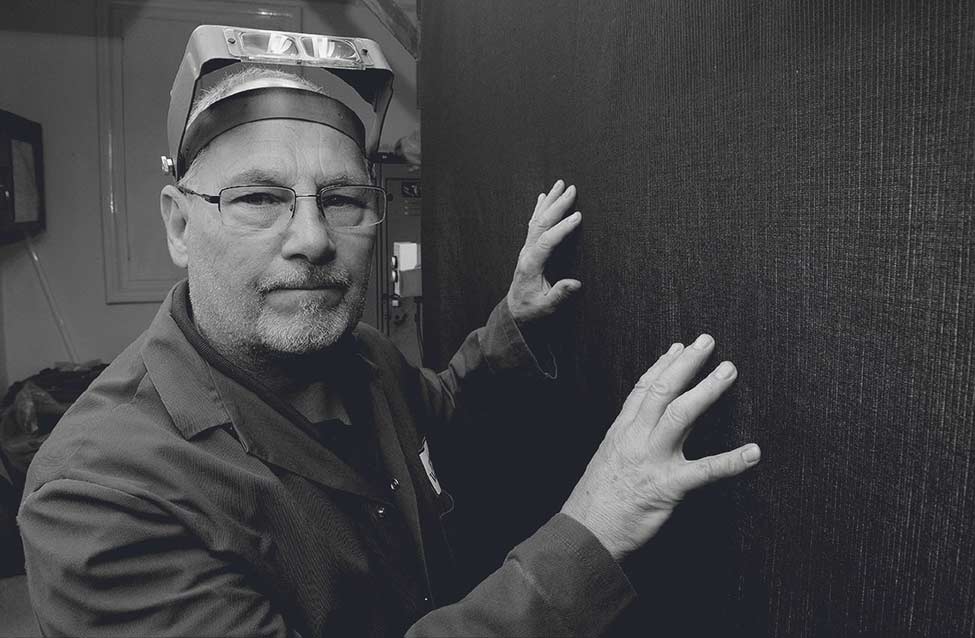

Darning

The darners meticulously inspect the fabric using a powerful magnifying device which allows all the fabrics to be repaired by hand, using a needle.

Burling

At the same time as darning, all the knots are removed to ensure a perfectly smooth surface for finishing.

Finishing

This involves transforming the raw fabric coming off the loom into finished fabric that can be used to make clothing. Dormeuil uses more than 50 different finishing techniques, including high pressure washing, stabilisation treatments, steaming and singeing.

This is where the very rarest fabrics come into their own, ready to be fashioned into the finest garments.